Setting an internal carbon price is a powerful way to assess your climate liability, prepare for future climate regulation and raise funds for low-carbon initiatives to mitigate your carbon impact. But how should you approach creating one, and what figure should you use? As Nick Daniel writes, Abatable has created a new guide to help.

More and more companies are getting a handle on their impact on the climate by measuring and disclosing their greenhouse gas emissions across the different emissions scopes of their business.

However, the lack of a consistent global price on carbon creating a cost on those emissions means that taking the next step – action – can often be an arbitrary choice.

As Abatable’s latest in-depth guide on internal carbon pricing demonstrates, forward-thinking businesses are now taking action by setting their own internal carbon price (ICP), with benefits extending from better decision-making to preparedness for future climate legislation.

An ICP is a mechanism where a company voluntarily assigns a monetary price per tonne of CO2 emissions from its operations and value chain. This can take multiple forms – from a shadow price to ensure the impact of future carbon price regulation is accounted for in decision-making, to an internal carbon fee or levy to raise funds for climate action.

Taking ownership of CO2 with an ICP ensures it is reflected on balance sheets, rather than contributing to climate change as an un-tracked business externality. It can help forward-thinking companies prepare for future climate regulation, control costs, mitigate risk and help fund low-carbon initiatives.

How can internal carbon prices be used?

As our guide outlines, different companies use ICPs in different ways. Some businesses use them hypothetically – i.e., as a decision-making tool to understand carbon risk and prepare for it when making investment decisions.

Others use them as an actual internal levy that is directly charged to specific business units, the proceeds of which are then designated to fund internal or external emissions reduction projects.

Currently, setting a ‘shadow price’ on carbon, is the most common approach, according to non-profit CDP. However setting up an internal levy is a powerful vehicle to fund climate action. As we’ve argued, taking one small example, if the 1,097 companies with a science-based target in 2022 set an ICP of $50 (covering Scope 1 and 2 emissions), and dedicated 10% of the resulting budget to external climate investments, $2.1bn would be immediately directed towards international climate finance.

Who uses internal carbon prices, and why?

Even the oil and gas industry, a heavy emitter that would be significantly impacted if carbon pricing was adopted more broadly by policymakers, has a long history of using internal carbon prices to inform investment decisions.

The UK oil major bp, for example, currently uses a $50 per tonne shadow price on carbon (updated from $40 in 2020), stemming from an internal emissions trading system it set up in 1998. bp uses carbon prices rising to $100 per tonne in 2030 and $250 per tonne in 2050 for its operational (i.e. Scope 1) emissions in certain investment cases.

Elsewhere, technology firms with relatively low emissions intensities and high profits are using internal carbon pricing to raise cash and fund nascent carbon removal solutions, from direct air capture to biochar. Microsoft, for example, which has set a goal to be carbon negative by 2030, has used an internal carbon price on its Scope 1, Scope 2 and business air travel emissions since 2012. Each department has a carbon budget, and fees are charged at different rates based on the type of emitting activity.

Other companies are more ambitious. Insurer Swiss Re set an internal carbon price of $100 in 2020 – rising from a previous level of $8 – making it the first multinational company to adopt a three-figure self-imposed carbon levy on Scope 1 and 2 emissions. The price now sits at $145 per tonne and will rise to $200 by 2030. The move was followed by a commitment for the company’s investment portfolio to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 and to phase out thermal coal from its reinsurance globally by 2040.

Swiss Re set an internal carbon price for two reasons – to incentivise internal emissions reduction schemes and to raise funds to support the increased purchase of carbon removal credits.

Other companies utilising ICPs include:

- Unilever, which uses an internal shadow price of €70 ($77) per tonne to inform its investment strategy;

- Iceland’s National Power Company Landsvirkjun, whose internal shadow carbon price moved from $30 per tonne to $144 per tonne in 2023;

- Finance firm Klarna, which has set a price at $100 per tonne to fund external climate initiatives including reforestation and renewable energy installations in developing countries.

Read more examples by downloading our white paper.

A growing trend

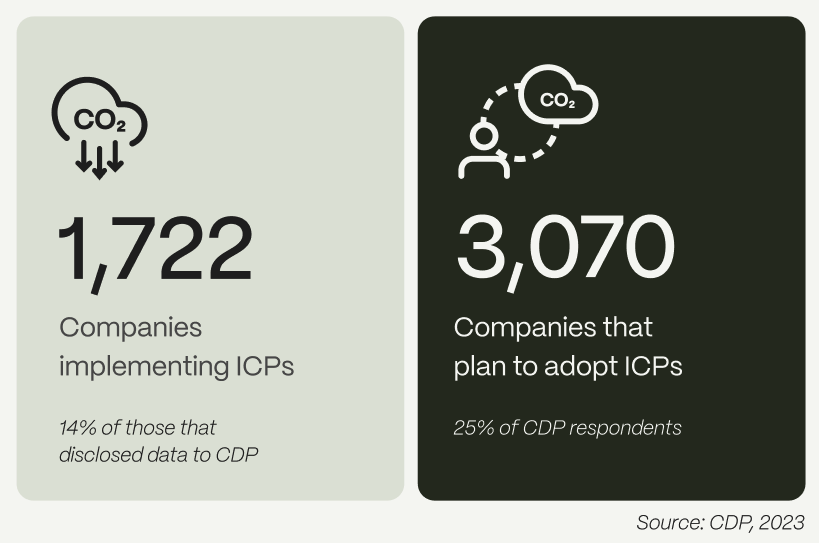

Internal carbon pricing adoption has significantly increased over the last five years, with 1,722 companies globally reporting to CDP that they have already implemented an internal carbon price as of 2023, representing 14% of the companies that disclosed their climate data. Moreover, an additional 3,070 companies (25% of respondents) indicated plans to adopt internal carbon pricing mechanisms. Around half of the 500 companies in the FTSE Global All Cap Index factor in some form of internal carbon pricing into their business plans.

It’s important to note that internal carbon prices should not be seen as static and can evolve over time in line with decarbonisation ambition and climate science. Indeed, CDP states that the majority of companies use evolutionary pricing which increases over time.

CDP also found a correlation between those companies setting an internal carbon price and those taking other actions to reduce emissions. The power sector is one of the main users of internal carbon prices, and these have had impacts on business decisions including closing down power stations due to profitability concerns.

Early evidence suggests ICPs drive results. An in-depth study of 500 US companies found that those using ICPs achieved a 13.5% reduction in CO2 emissions per employee, and 16% per unit revenue, compared to peers.

What level should an ICP be?

There are no standards and limited guidance on how to set an internal carbon price, so how to approach it is largely up to the company and its drivers for doing so – whether these are to account for future climate policies or create a fund for climate action.

As generation foundation, Ecofys and CDP outline, the method you use will depend on your reasons for setting a price. If you are hedging for carbon risk, choosing a price aligned with compliance schemes such as the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) would be a sensible strategy, though it’s worth noting the price of carbon in compliance schemes varies around the globe. If you are setting a price to facilitate emissions reductions or to create a fund to support climate action, this needs to be meaningful enough to effect change.

There are a number of specific approaches to setting an ICP:

Use compliance carbon pricing schemes as a proxy

The EU ETS, mentioned above, the world’s largest carbon trading scheme in terms of traded value, is a cap-and-trade system with a price hovering around €80 ($90) at the time of writing. EU ETS prices have pushed €100 over the last two years – which is in line with where carbon prices need to be to spur meaningful action on climate change.

Other countries importing goods such as steel into the EU will begin to pay that price for the emissions associated with the imported products under the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) scheme.

Thus, the ETS is a good starting point for companies with customers in Europe to aim towards.

In North America, Canada’s Federal-level carbon tax sits at CAN$80 ($55), which is set to rise to CAN$170 by 2030.

Certain countries have set flat carbon taxes for various sectors with higher prices. Sweden, for example, has set a carbon tax on fossil fuel production of SEK1,368 ($127). Norway has a similar level of $107.

Hedge against future price rises

The expectation is that carbon prices in compliance schemes and in the voluntary carbon market will rise. The Bank of England has said that companies should prepare for a world where carbon prices exceed $150 per tonne by 2030. This is against a backdrop of governments requiring an increasing number of companies to disclose information about their emissions ahead of ambitious 2030 emissions-reduction targets.

The High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices has estimated that companies would need to set internal carbon prices of $100 per tonne by 2030 to reduce emissions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change. This is the figure used by the World Bank in its guidance on setting a shadow price on carbon in economic analyses.

Set an implicit price

This approach sees companies calculate how much they are spending on emissions reductions already, including to meet government regulations, and then extrapolate this across the business.

Implicit prices are calculated retroactively based on the costs of renewable energy and energy efficiency investments, for example, and spending on climate projects.

Use the social cost of carbon

If the price paid to emit a tonne of CO2 adequately reflected its impact on the planet, it would be set at the social cost of carbon – the discounted net present value of the future damages created by a tonne of CO2 emitted into the atmosphere.

But what is the social cost of carbon? This is a non-trivial question whose answer is dependent on a multitude of factors including the assumed climate sensitivity (the amount of warming associated with a given level of CO2 in the atmosphere) and the discount rate used to value climate change damages in the future.

What is certain is that the social cost of carbon is higher than the examples provided above.

The landmark Stern review on the economics of climate change in 2006 used a social cost of carbon of $85 in 2000 prices (around $150 in today’s prices).

The UK government today in its Green Book, which is used as a policy and project appraisal framework, uses a carbon price of £260 ($321) for 2025.

How should I implement an ICP strategy?

Implementing an internal carbon price involves more than picking a number. It requires careful design and change management to ensure the price influences decisions and gains traction across the organisation.

There are several practical strategies to successful ICP programmes:

- Define clear objectives and scopes

- Determine the right price level (and adjust over time)

- Integrate ICPs into financial processes

- Secure buy-in through engagement and co-benefits

- Start small and scale up

- Implement complementary policies and systems

We explore these, alongside take-away actionable insights for sustainability and procurement leaders, in detail in our ICP white paper: Internal carbon pricing – A strategic tool for corporate climate leadership. Download it here.

If you want to use your ICP revenues to support external climate action, Abatable can help. Get in touch with us to understand how we can help you find and purchase suitable high-integrity carbon credits through our integrated sourcing and procurement solutions.

Read our CEO and Co-founder Valerio Magliulo on the importance of businesses setting an internal carbon price in Environmental Finance.