Communicating about your use of carbon credits is important to improve transparency in the industry but, in an era of greenhushing, how can you do so with confidence? In the third of our four-part corporate buyers series, Bryan McCann breaks down the claims state of play.

Debates continue on how carbon credits should fit into corporate sustainability strategies. A consensus has emerged: credits are a complement, not a substitute, for internal greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

When used responsibly, carbon credits allow companies to go beyond what is technically or practically feasible within their own operations. They enable funding of global climate action, supporting communities, and contributing to nature preservation and restoration. Given the $8.4tn climate finance gap, this is a lever we should utilise fully.

For companies, credits offer more than just compliance with carbon pricing schemes. They can accelerate net-zero strategies, strengthen social licence to operate, and compensate for product-related emissions. But, as Apple recently experienced, challenges remain:

- How can companies make credible claims while avoiding accusations of greenwashing?

- Who are the main arbiters of the use of credits?

- What are the main principles and standards that companies should follow?

Types of climate claims

Apple opted to market its Apple Watch Series 9 in 2023 as ‘carbon neutral’, after it cut product emissions by 75% and then moved to use credits under leading standards with third-party validation. After it was challenged on the use of the term, in a landmark move, the US Environmental Defence Fund (EDF) is legally backing Apple’s carbon-neutral claim, marking the first time an environmental NGO has defended a company’s offset strategy in court.

Carbon neutral is one of a number of main claims companies make based on their approach to emissions reduction and carbon credit use (see footnote 1):

Carbon neutral

This indicates you’ve measured your emissions and offset them, typically on an annual basis. I.e. any CO2 emissions released into the atmosphere from your activities are balanced out by an equivalent amount of emissions reductions or removals.

Net zero

Net zero differs from carbon neutral in that it typically is larger in scale, referring to balancing out all greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere at a global scale. To credibly claim net zero, you must set science-based targets, reduce emissions across your value chain, and only use removals for residual emissions once your emissions have been reduced by 90-95% (depending on your industry’s net zero pathway).

Climate contribution

This approach is emerging as an alternative to traditional offsetting claims. Under a climate contribution model, companies openly acknowledge their emissions, work to reduce them, and invest in carbon credits as a way to contribute to global climate efforts, without suggesting they’ve cancelled out all their impact. This framing recognises the vital role of carbon markets in scaling climate finance.

Read more about how carbon credit buyers approach claims and other aspects of procurement in our report: What leading carbon credit buyers do differently

What should you look for in claims guidance?

There are four main sources of guidance shaping the claims landscape:

- Net-zero standards: Pathways for reducing Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions – however these often stop short of addressing the use of credits.

- Independent best practice: Codes of conduct for credit use that set expectations, but are not necessarily adopted by all companies using credits.

- Auditable claims standards: Frameworks that provide clear, verifiable and internationally recognised rules for claims like carbon neutrality.

- Governments: Which provide a mix of principles, codes of conduct, and legislation, depending on the jurisdiction.

Across these different sources, strong claims guidance should do four things:

- Focus on companies reducing emissions first before taking action towards making carbon neutrality claims;

- Provide guidance on the types of carbon credits being used, effectively providing a minimum bar on quality;

- Recognise the importance of additional climate action; and

- Be specific regarding what companies can and cannot say after they buy credits.

The landscape can seem bewildering, but greater clarity is emerging thanks to standard-setters and policymakers. Below we summarise the key frameworks companies should be aware of.

Net-zero standards: The SBTi baseline

The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) is the most widely adopted net-zero framework, with over 11,000 companies setting targets and more than 8,000 validated.

SBTi’s flagship Corporate Net Zero Standard provides a science-aligned pathway for companies to reduce their internal emissions. SBTi also provides detailed sectoral guidance for various industries, such as Forestry, Land, and Agriculture (FLAG) and Apparel and Footwear.

Crucially, SBTi is focused primarily on internal emissions reductions – that is, reductions within companies’ own value chains, also known as their Scope 1 (direct emissions) and Scope 2 (emissions from electricity and fuel use). Scope 3 emissions – often the largest Scope – come from a company’s suppliers and customers.

The standard is quite clear that it excludes the use of carbon credits, which under SBTi must be reported separately from the GHG inventory and do not count as reductions toward meeting near-term or long-term science-based targets. Carbon credits can only be considered as an option for neutralising residual emissions (those remaining at the end of a company’s decarbonisation journey) or to finance additional climate mitigation beyond their science-based targets.

Guidance on the use of credits is only provided at the point of net zero, where SBTi says companies must permanently neutralise their final ~10% of residual emissions using removal credits.

SBTi does not validate the use of credits on the way to net zero, i.e. in the 25 years between 2025 and 2050, the endpoint of most net-zero targets. It uses the term ‘Beyond Value Chain Mitigation’ (BVCM) for any use of credits before the target net-zero date. While SBTi ‘recommends’ that companies deliver BVCM, it neither counts credits towards targets nor does it plan to validate BVCM claims.

Despite a highly-publicised declaration from SBTi’s trustees in April 2024 that it would consider the use of carbon credits, and a major revision of its Corporate Net Zero Standard is expected to be finalised in Q1 2026, Abatable’s view is that SBTi will continue to prioritise internal reductions over validating credit use.

This marks a significant gap. 2050 is over two decades away and, in many industries, the technology does not yet exist for companies to fully decarbonise. Even if a company managed to reduce its emissions by 2% according to its science-aligned pathway, that leaves the other 98%.

Investing in carbon credits would fund crucial emissions reductions elsewhere. As the Environmental Defense Fund outlines: ‘Ultimately, we need to continuously maximise investment in the most urgent and the most impactful activities: those that drive systemic change. The vital and growing role of the voluntary carbon markets in delivering emissions reductions, avoidance and removals should be recognised, enabled and accelerated.’

For companies looking to take responsibility for their ongoing emissions, other guidance is crucial.

Independent best practice: VCMI, the Oxford Principles for Offsetting

The Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI), launched in 2021 at COP26, provides the clearest guidance on how companies can use credits as an addition to their internal emissions reductions. Its Claims Code of Practice sets expectations: companies must reduce internally first, then use credits to cover remaining emissions. This approach reflects the mitigation hierarchy, backed by broad industry and policy support.

The Claims Code of Practice, launched in 2022, lays out best practice for corporate claims. The mission is simple: ‘Companies must take responsibility for how carbon credits factor into net-zero transitions, so their use accelerates – and does not delay or displace – decarbonisation’.

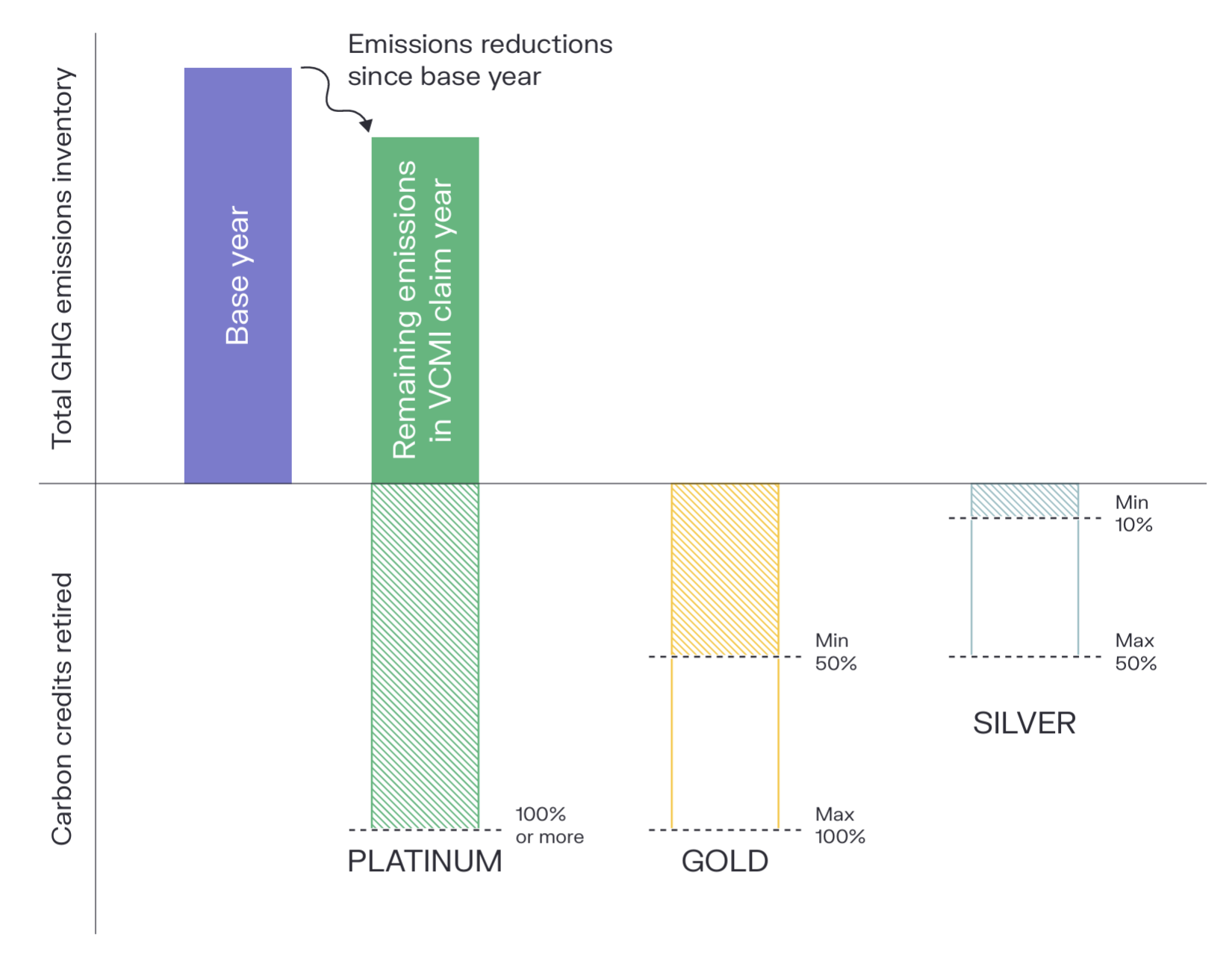

While the Claims Code itself provides a significant amount of detail – along with silver, gold and platinum tiers of claims depending on the amount of credits purchased and retired – the sentiment is simple. Companies should:

- Know what their emissions are;

- Set emissions reduction targets and take direct decarbonisation action against these; and

- Purchase and retire carbon credits for some portion of their remaining emissions.

Carbon Integrity Silver, Gold and Platinum Claims, and the respective thresholds that represent the amount of credits retired, proportional to the remaining emissions in the year that a company makes a claim, having reduced emissions in comparison to the base year. Source: VCMI

They should reduce internally first, then take responsibility for their remaining emissions, in line with the mitigation hierarchy.

The Claims Code is notable for two reasons:

- It clearly requires internal reductions first before purchasing credits; and

- It creates consensus across industry experts and scientists to establish a market norm.

The incorporation of the viewpoints of a range of actors (VCMI is backed by several foundations, the UK Government, and Google) means that the recommendations have a broad base of support and represent a reasonable compromise across various opinions.

Claims can also be calibrated based on the quantity of carbon credits purchased (see footnote 2), providing an opportunity to engage for companies with limited budgets or sizable footprints.

For the quality of credits, VCMI points to projects approved under the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market’s Core Carbon Principles. As that programme ramps up, those approved for use under the UN-backed CORSIA scheme for international aviation emissions can also be used in the interim (see footnote 3).

Finally, VCMI also provides guidance for how companies can use carbon credits to address their Scope 3 (supplier and customer) emissions, which can account for as much as 70% of companies’ emissions. As these are outside of a given company’s control, they are often challenging to address. Under this supplementary guidance, provided companies are implementing efforts to reduce their Scope 3 emissions and are disclosing those efforts, they can still be recognised for their efforts.

While the most prominent, VCMI is but one of several pieces of guidance to support corporate use of credits (or ‘high integrity demand’), all of which generally follow the same approach.

Oxford Principles for Offsetting

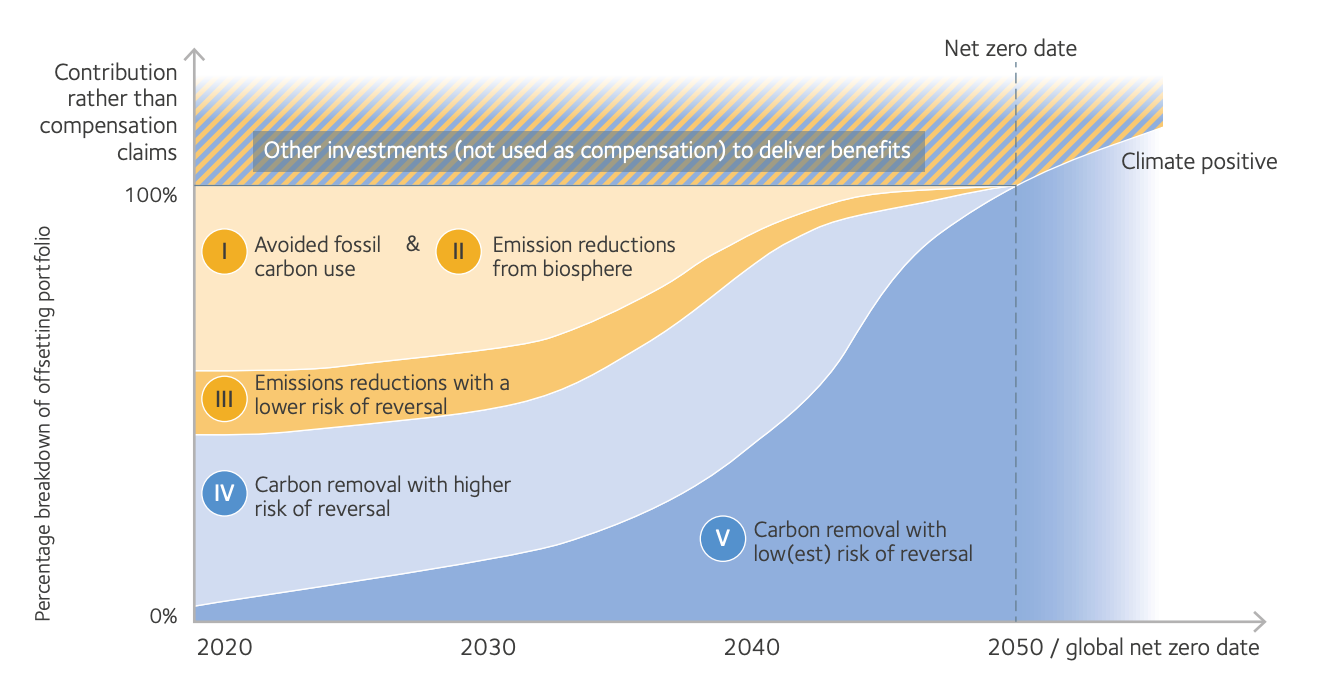

Another source of best practice is the Oxford Principles for Net Zero Aligned Carbon Offsetting. They are not claims guidance per se: they do not specifically govern what companies can say when they buy credits. However, they do provide detailed guidance on what types of credits companies should buy and how their purchasing should evolve over time. They also reinforce the notion of companies prioritising internal reductions over the use of credits.

How the Oxford Principles outlines the use of both carbon reduction and removal credits as companies approach 2050. Source: The Oxford Principles for Net Zero Aligned Carbon Offsetting (revised 2024)

Under the Oxford Principles, companies are encouraged to increase the proportion of carbon removal credits they are purchasing as they approach their net-zero target date. Moreover, they should also shift to removals with durable storage (think technologies that convert CO2 into rock) versus removals like tree-planting, where there is risk of natural disturbances to the carbon stocks.

We broadly agree with these recommendations, though we caution that we cannot lose sight of the need to massively reduce emissions today while also inventing the technologies needed for net zero tomorrow.

A key limitation, however, of VCMI and others is that they are not necessarily auditable and do not provide for product-level claims (e.g. carbon-neutral watches). That is where ISO comes in.

Auditable claims standards: ISO 14068

In 2023, ISO, the global standard-setting federation, released a carbon neutrality standard called ISO 14068. This provides rules for how companies can use credits to make enterprise-wide or product-specific carbon neutrality claims.

ISO has issued over 25,000 standards governing manufacturing, technology, food safety, and more, from the measurement of the fat content of cheese (ISO 23319) to determining the strength of ceramic ball bearings (ISO 19843).

An ISO standard is the result of complex deliberations from international technical committees and subcommittees acting on behalf of the 167 member countries. Only once passing a lengthy feedback and approval process are ISO standards agreed and made usable by the public.

ISO 14068 generally follows the same approach as VCMI: first, internal reductions, then carbon credits. It is anchored around the term ‘carbon neutrality’, where companies reduce their own company-wide emissions – or the emissions of a specific product – and offset the residual emissions.

There are rigorous requirements under the standard that companies must meet, including company-wide commitments, continual improvement of their carbon neutrality plan, and robust short and long-term targets. Only then, and once their activities have been validated by a third party, can companies call themselves or their products carbon neutral.

Credits must meet the core requirements of being real, verifiable and transparent, with flexibility on whether companies wish to use credits that reduce emissions elsewhere or remove them from the atmosphere completely.

Companies such as Zipair in Japan have already adopted ISO 14068, and companies including Danone are expected to transition from its predecessor PAS 2060 in the coming years.

Robust standards like ISO 14068 are increasingly being coupled with government rules to create a robust framework for corporate credit use.

Governments: rules, risks and leadership

Ultimately, any corporate public sustainability-related declaration must fall under the purview of governments. So-called greenwashing is, in effect, false advertising, which governments have been regulating for over a century.

There are a plethora of overlapping national rules and regulations for sustainability-linked claims.

Canada provides a compelling model. In 2024, the country passed into law new anti-greenwashing legislation. We believe this is the most comprehensive carbon credit framework globally. Claims must use evidence that is ‘suitable, appropriate, and relevant to the claim’, underpinned by an internationally recognised methodology (such as ISO 14068). Carbon credits must represent real, additional, and permanent emissions reductions with clear calculations for how they were calculated. Simply put, companies must ‘be truthful’ and ‘ensure claims are properly and adequately tested’.

This legislation is new. How it will be implemented will evolve over time through the courts and the claims brought before Canada’s Competition Bureau. It does, however, provide clarity on the claims companies can make, and with clarity comes the certainty needed to underpin ambitious corporate investment in climate action.

The EU was pushing ahead with its proposed Green Claims Directive, which was expected to define several carbon credit claims, such as carbon neutral and net zero, however this was put on hold in June 2025. Under the Directive, carbon credit and other environmental claims were to be substantiated through mandatory scientific substantiation and third-party verification. The European Commission announced its intention to withdraw the proposal, following political opposition over concerns about regulatory burden, particularly regarding pre-verification requirements and the inclusion of microenterprises.

The Directive’s future remains uncertain and, at the time of writing, it could be delayed, reworked, or abandoned, though other EU anti-greenwashing rules remain in effect.

Other countries, such as Singapore, have opted to provide dedicated principles for the use of carbon credits. Earlier in 2025, the Singapore Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI) launched a consultation on a new set of principles for the role of carbon credits in corporate decarbonisation action.

These broadly follow VCMI and ISO in that companies should use credits only after they have made internal reductions. They also demonstrate unequivocal support from the Singapore government for companies’ participation in well-functioning carbon markets.

However, unlike ISO and VCMI, the Singapore guidance makes clear that carbon credits are only to be used as a last step, and that companies need to ‘prioritis[e] all feasible emissions reductions across all scopes before considering the use of carbon credits’.

Tone matters, and companies should be recognised and rewarded for their climate investments, both inside and outside of their value chains, provided they are coupled with ambitious internal reductions.

Abatable in action: Paris 2024

Abatable is well-equipped to help companies think through the credits they wish to purchase and the claims they wish to make.

In 2024, Abatable was the carbon crediting partner for the Paris Olympic Games. This involved helping the organisers design a climate contribution approach, coupling climate action with clear messaging on impact.

The organisers did not wish to use the term carbon neutral, but still wanted to fund projects supporting positive impact for local communities, biodiversity, and human health. This claim is modest in nature, but it still resulted in over 12mn euros invested, funding 1.59mn tonnes of emissions reductions.

We also helped source and vet these projects, providing for quality impact alongside high integrity demand.

The takeaway for corporates

Carbon credits are a powerful tool to complement internal decarbonisation. The standards and guidance emerging today provide a clearer path for companies to use them credibly – from net-zero roadmaps to auditable neutrality claims.

At Abatable, we help corporates navigate this evolving landscape, source high-quality credits, and design claims strategies that balance ambition with integrity as part of our Plan and Communicate and report procurement solutions.

Read the other articles in our corporate buyers series:

- Navigating carbon credit integrity: What every buyer needs to know

- How to run an RFQ to access high-quality carbon credits, faster

- How to talk to your CFO about your carbon budget

Read more about how carbon credit buyers approach claims and other aspects of procurement in our report: What leading carbon credit buyers do differently.

If your organisation is considering how to use credits in its net-zero journey, get in touch with us to explore how Abatable can help.

Footnotes

1. There are others, including ‘climate positive’, ‘forest positive’, and ‘carbon negative’. However for this article we have focused on these three as they have the most robust protocols against them.

2. Carbon Integrity Silver (≥ 10% and < 50%); Carbon Integrity Gold (≥ 50% and < 100%); Carbon Integrity Platinum (≥ 100%)

3. Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), administered by the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). Similar to ICVCM, under CORSIA, various carbon credit standards and methodologies are reviewed and, should they not meet CORSIA requirements, excluded from use.